The Icon of the Holy Trinity (Philoxenia of Abraham) by Andrej Rublev (1370-1430)

The Meditatio Centre, London, 16 december 2017

by Joris Van Ael

Listen to this talk on SoundCloud »

I. The Icon of Andrei Rublev, rooted in Tradition.

A. Historical Survey

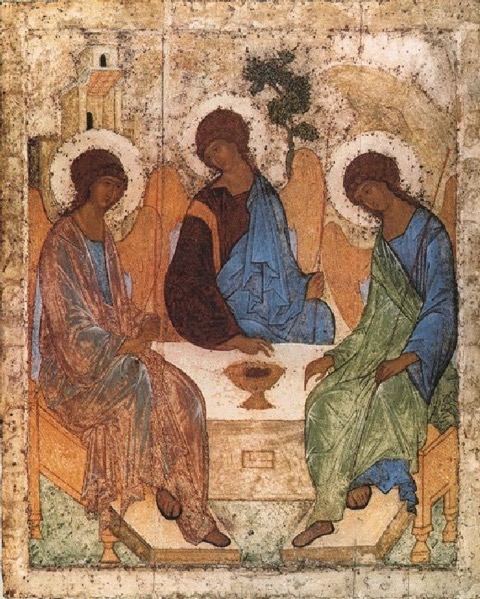

The famous icon of Andrej Rublev, known as 'the Philoxenia (hospitality) of Abraham’, or with the more common name 'The Trinity’, belonged originally to the monastery of the Holy Trinity at Sergej Posad, founded by Sergej of Radonesj in 1310. The icon was made for the iconostasis of the new church, built in stone, which replaced the original wooden church of Sergej of Radonesj.

We know very little about the life of the painter. He was born around 1370 in the neighborhood of Pskov, in the very North of Russia. He grew up during the liberation war against the Tatars, central Asian tribe-people that devastated the country. They were defeated in the battle of Kulikovo in 1380 by Dimitri Donskoj1, who was able to unify the territories with Moscow as center. Nevertheless the monastery was devastated in 1393, one year after the departure of St. Sergius and another time in 1408.

1 Saint Dmitry Ivanovich Donskoy (Russian: Дми́трий Ива́нович Донско́й,also known as Dimitrii or Demetrius), or Dmitry of the Don, sometimes referred to simply as Dmitry (12 October 1350 in Moscow – 19 May 1389 in Moscow), son of Ivan II the Fair of Moscow (1326–1359), reigned as the Prince of Moscow from 1359 and Grand Prince of Vladimir from 1363 to his death. He was the first prince of Moscow to openly challenge Mongol authority in Russia. His nickname, Donskoy (i.e., “of the Don”), alludes to his great victory against the Tatars in the Battle of Kulikovo (1380), which took place on the Don River. He is venerated as a Saint in the Orthodox Church with his feast day on 19 May (Wikipedia)

In 1392, Father Nikhon became the second abbot of the Trinity-Lavra. The Young Andrej placed himself under his guidance and entered the monastic life.

We know almost nothing about his artistic and iconographic formation. We can suppose that he was in contact with Byzantine masters working in Russia, but also that he may have travelled to Contantinople and perhaps to Mistras seen the evidence of influence of the Palaeologian Renaissance in his work, which flourished during the last dynasty (the Palaeologians) of Byzantine emperors. In that period a new dynamism entered the classical Byzantine style of the Macedonian school. Human sentiments gained more importance and this became visible in the way traditional themes were treated.

(In the West the same happened from the 12th century on. St Bernard of Clairvaux, St Francis of Assisi and others inaugurated this special tone of tenderness in the Christian mind and influenced indirectly the Christian art.)

Rublev travelled around, probably with a team of craftsmen and painters and worked in several important cathedrals.

In 1405, together with Theofan Grek and Prochor of Gorodetz he worked in the Annunciation Cathedral of the Moscow Kremlin.

In 1408 he painted in the Cathedral of the Dormition in Vladimir. A fresco of the Last Judgment remains, together with some panels of the Deësis-range.

In 1410 he painted in the cathedral of the Mother of God in Zvenigorod. Only the central icon of Christ survived, though very much damaged, together with the icons of the Archangel Michaël and Saint Paul.

At the end of his life he was involved in the decoration of the new church of the monastery at Sergej-Posad. He painted the feast-range and the Trinity-icon and probably more icons which are lost.

The monk and painter Andrej Rublev died in 1430 and was buried in the Andronevsky-monastery near Moscow.

Important is that during the Stoglav Synod of 1551 the fathers proclaimed that Rublev’s way to represent the Trinity was the only valuable and should be the model for all later representations.

In 1988 Andrej Rublev was numbered among the saints. He was canonized at the occasion of the millennium of the Christianization of Russia. His feast is celebrated on the 14th of July.

B. What does the icon represent?

The icon represents the narrative of Genesis 18, 1-16, the hospitality of Abraham. The text relates how three men presented themselves at Abraham’s tent, erected near the Oak of Mamre, while he was resting during the hottest hour of the day and how Abraham offered them hospitality.

Very soon in early Christianity the narrative by some was interpreted as a prefiguration of the Trinity.

Different elements sustained this reading of the text:

- First the number three, that in early Christian minds was spontaneously linked with the three Persons of the Holy Trinity.

-

There is also the remarkable interchanging of the way the angels are addressed to, or spoken of. Sometimes in the singular, as if they were one person, sometimes in the plural form. One time the text speaks about the visitors as 'He' another time as 'They'. This interchanging became an important reason for the allegoric or Trinitarian reading.

He had a vision of the Lord, too, in the valley of Mambre, as he sat by his tent door at noon. He looked up, and saw three men standing near him; and, at the sight, he ran from his tent door to meet them, bowing down to the earth. [1] Lord, he said, as thou lovest me, do not pass thy servant by; let me fetch a drop of water, so that you can wash your feet and rest in the shade. I will bring a mouthful of food, too, so that you can refresh yourselves before you go on further; you have not come this way for nothing. And when they had agreed to what he proposed, Abraham hastened into the tent to find Sara. Quick, he said, knead three measures of flour, and make girdle-cakes. Meanwhile, he ran to the byre, and brought in a calf, tender and well-fed, and gave it to a servant, who made haste to cook it. Then he brought out butter and milk with the calf he had cooked for them, and laid their meal ready, and stood there beside them in the shade of the trees.

- The three angels, visiting Abraham and Sarah came to announce the imminent conception and birth of the 'Child of the Promise', Isaac, who is a prefiguration of Christ the incarnated Logos.

- In the Letter to the Hebrews, the writer makes allusion to the narrative of Genesis and emphasizes the importance of the virtue of hospitality: "How Abraham, not aware who his visitors were, offered hospitality to angels" (Hebr 13, 3). Since then the duty of hospitality hides a revealing force, clarified by Christ Himself when He said: "I was a stranger, and you took me in" (Mt 25, 35b). The icon of the 'Hospitality of Abraham' sustains this important aspect: the identification of Christ-God with the stranger, especially when Abraham and Sarah are represented, serving the three visitors.

Not all the exegetic schools of the early Church were ready to interpret the narrative in an allegoric way, as a prefiguration of the Holy Trinity.

The position of the school of Antioch was very sober: the three men were angels, messengers of God. The Antiochenes avoided far-stretching interpretations. Saint John Chrysostom in the 4th century emphasizes the relativity of the way Abraham addresses one of the three as 'Lord’. Theodoretus of Cyrrh even indicates how it is a common thing to address an important person as 'Lord’. Nevertheless, behind the angels hides the Presence of the divine, as the message they deliver shows.

The second exegesis is typological or Christological. In the Old Testament every theophany, every apparition of God is in fact a christophany. It is the incarnated Logos that appears before the incarnation happened in time. So, as the text permits it, one of the messengers is set apart from the others: “only one of the angels was really God, Lord and Judge, and He alone was adored by Abraham, and this 'Lord from Lord’ was the Son of God”. (Hilarius of Poitiers).

This is the opinion of a whole range of church-fathers as Tertullian, Justin the Martyr, Origen and Hilarius of Poitiers. Cyrillus of Jerusalem considers the central angel as the prefiguration of the Incarnated Lord. This view is supported by the context of annunciation of the birth of the 'Child of the Promise’. The laughing of Sarah symbolizes the jubilation of mankind at the birth of the Messiah.

The 3d way of reading the text is as a clear prefiguration, the early revealing of the mystery of the Holy Trinity.

This reading could lead back unto Philo the Jew, who saw in the central angel the Father of the universe and in the two others the creative and royal forces of the Father: God, and two aspects of Gods. Origen gives an opening for this interpretation: “There, he says, the mystery of the Trinity is prefigurated”, and Cyrill of Alexandria: “He adressed one Lord, the one nature of God, although he saw Three”.

96. Abraham, ready to receive strangers, faithful towards God, devoted in ministering, quick in his service, saw the Trinity in a type; Genesis 18:2 he added religious duty to hospitality, when beholding Three he worshipped One, and preserving the distinction of the Persons, yet addressed one Lord, he offered to Three the honour of his gift, while acknowledging one Power. It was not learning but grace which spoke in him, and he believed better what he had not learned than we who have learned. No one had falsified the representation of the truth, and so he sees Three, but worships the Unity. He brings forth three measures of fine meal, and slays one victim, considering that one sacrifice is sufficient, but a triple gift; one victim, an offering of three. And in the four kings, Genesis xiv who does not understand that he subjected to himself the elements of the material creation, and all earthly things in a sign whereby the Lord’s Passion was prefigured? Faithful in war, moderate in his triumph, in that he preferred not to become richer by the gifts of men, but by those of God. (De excessu fratris sui Satyri, II, 96)

But since three men appeared, and no one of them is said to be greater than the rest either in form, or age, or power, why should we not here understand, as visibly intimated by the visible creature, the equality of the Trinity, and one and the same substance in three persons? (Augustinus, De Triniate, II, XI, 20)

Maximus the Confessor: God appeared to Abraham as Three, but adressed Him as One.

C. Short survey of the iconographic tradition up to Rublev.

The different ways of exegesis of the narrative of Gen 18 are reflected in the iconographic approach. They appear mostly mixed up in one and the same image. Especially the Christological and Trinitarian interpretations are interwoven.

The factual story is always the basis, as in exegesis the literal reading is the starting point. The most important elements of the narrative are always represented. They gain slowly symbolical and mystical, even liturgical meanings.

Some examples of the iconographic history of the icon.

1. The catacombs of the Via Latina.

- Not yet angels

- the isokephalia

- The angel in the middle could represent the Son. He has a smaller stature than the other two. It is a common way in paleochristian art to represent Christ as a childish figure, 'the Child of God', which is the incarnated Son.

- The calf immolated by Abraham as meal for the visitors is also represented.

2. Santa Maria Maggiore.

- The south wall of the basilica is decorated with an Abraham cycle. We see two scenes: the welcoming of the visitors by Abraham and the meal offered. The table has the form of a 'mensa', a paleochristian altar.

- In the first scene the central figure is set apart by a mandorla.

- In the second scene there is no distinction between the three.

- We see the three breads baked by Sarah and the one calf offered by Abraham. The oak and the house.

- In the first scene the Christological exegesis prevails, in the second the trinitarian.

- Important is the square table.

3. Ravenna

- The same elements are there.

- The location of the Abraham narrative, together with the sacrifice of Isaac, the offerings of Abel and Melchisedech put the scene in a liturgical/Eucharistic context.

4. Capella Palatina of Palermo

- The same elements.

- the apparition of the chalice: an important addition that will be exploited by Rublev

- The 'genii' become angels. The central angel is set apart from the others by the color of the nimbus

5. The Codex Barbarini (1094) or the 'Oriental type’.

- Table in the shape of an 'U' . This was the shape of the altar in the Syrian Church.

- The angels are posted around the table which introduces a dynamism of relation between the divine visitors.

- The central angel is emphasized by his stature, by the cross in the nimbus. He wears also the garments traditionally given to Christ, purple and blue.

- Although the image carries the name 'Hagia Trias' (Holy Trinity) only the central angel is clearly identified as the Son. The two others seem less important and rather companions of the central one.

- All the other elements remain.

- This type of representation is also found in the bronze doors of the cathedral of Souzdal, on the walls of the monastery of St. John on Patmos, in the early icons of Novgorod and on the walls of the church painted by Theofan Grek at Volotovo.

6. Growing importance given to the equal value of the three angels.

- Göreme (Cappadocia): Three times the cross in the nimbus. Nevertheless Christ the Son is identified as the central angel, the two others are not identified. On top the inscription 'Hagia Trias'.

- Icon of the Benaki museum: The three angels are completely identic, sitting around the square table. Abraham and Sarah are serving.

- The icon of Pskov: refers to the older representations of Ravenna and Palermo, there is no conversation.

7. The Icon of Vatopedi (Mt Athos).

- Gives great importance to the dialogue, represents the scene in a liturgical setting. The table points towards the altar.

8. The manuscript of John Cantacuzenos.

- Abraham and Sarah are omitted; around the table, conversation. Central on the table, the calf in the chalice

- Equal emphasis on the three figures. Their stature is of equal importance. The central angel is identified as the Son by the garments and the cross in the nimbus.

9. The calf

- Important is the representation of the immolated calf, present in the whole tradition and often represented in a very explicit way.

D. The icon of Rublev, exterior description

At the historical level, following the narrative of the visit, Rublev keeps most of the traditional elements:

The tent (house of Abraham), the oak of Mamre, the mountain (where A’ham was with one of the messengers to overlook Sodom and Gomorrah), the meal, the calf in the chalice, the three men represented as angels and pilgrims, strangers (the staff). He is not withholding Sarah and Abraham. On the table is just the one chalice, all other attributes are omitted.

1. Some symbolic elements are also kept:

- The isokephalia,

- The central angel wears the garment traditionally given to Christ, blue and purple and the clavus. No cross in the nimbus, no name indicated.

- The square table.

2. What does Rublev emphasize?

- Emphasis on the conversation between the three, they do not look at the spectator, but an internal event is taking place.

- The equality in strength and presence of the three angels combined with the very clear distinction between them. Unity and distinction are emphasized with equal force.

- The whiteness of the table.

- The careful disposition of house, tree and mountain, respectively linked to the three figures.

- The equal strength of the three leads unavoidably to personal identification, in a logic respect for the doxology: Glory to the Father, to the Son and to the Holy Spirit.

- Only one chalice with the immolated calf.

II. Theological and spiritual reading of the icon of Andrej Rublev.

A. Theologia and oikonomia

Pseudo- Dionysius. D.N. 588C:

Now as I have already said, we must not dare to apply words or conceptions to this hidden transcendent God. We can use only what scripture has disclosed. In the scriptures the Deity has benevolently taught us that understanding and direct contemplation of itself is inaccessible to beings, since it actually surpasses being. Many scripture writers will tell you that the divinity is not only invisible and incomprehensible, but also unsearchable and inscutable. And yet, on the other hand, the Good is not absolutely incommunicable to everything. By itself it generously reveals a firm, transcendent beam, granting enlightenments proportionate to each beings…

D.N. 588A

This is why we must not dare to resort to words or conceptions concerning that hidden divinity which transcends being, apart from what the sacred scriptures have divinely revealed.

B. The mystery of unity-diversity in the icon of Rublev.

- The unity. He presents the three messengers in a circle, symbol of unity, fullness and completeness, of indivisibility and divine perfection.

- Only the angel on the left exceeds the circle. This has to do with the Trinitarian theology of the East, where the Father is the eternal source of the Godhead. He communicates his own divinity to the Son and the Spirit.

- The isokaphalia: symbolizes the one will and the one operation of the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit.

- The blue color which is common to the three angels.

- The atmosphere of intense and perfect harmony which evokes realities as towardness, benevolence, mutual attention and obedience, unanimousness.

- The distinction is visible in the number three. Three is a mystical number that unites differences in unity.

- The three figures have clearly different garments, differentiated by different colors.

- They are seated in a fixed order which in no way means a kind of subordination. Rather the order emphasizes the life-giving distinction and otherness which blossoms in unity and mutual harmony.

C. The level of 'Oikonomia’

This level corresponds to 'God, the Coming One’, to God Who makes himself accessible. Out of the depths of His own will and desire, He makes an opening for being known and to mutual relationship.

Within the Great Counsel, the 'Sacra conversatio’, ongoing in God since all eternity, the decision is made to create a world outside Himself; a completely different world, not at all godly or divine, but subject to change and decay, material and transient.

Maximus Confessor, Cent. Char. IV,4

The Creator, when He willed, gave substance to and sent forth his eternally pre-existent knowledge of beings…. When He willed, He decided to act according the vigorous and creative energy which is his own.

1. The Sacra Conversatione

The icon shows this heavenly conversation, the Great counsel, in a symbolic way. Indeed, something is going on between the three angels. We clearly have the impression that the left angel, who symbolizes the Father, has the initiative in the conversation. He opens the dialogue. The other angels, together and in union with the Father and turning to Him, approve what is proposed and express their readiness to take a share in the execution of the 'plan of Salvation’, conceived in unanimity. This 'plan’ is unfolded in time. The first phase is the creation of the universe drawing it out of nothing (ex nihilo) into existence. By his Word he created and by his Spirit He dynamized all he brought into existence. From the beginning creation is a Trinitarian act.

The Son Himself will work out the plan of Salvation and the Spirit will be the co-worker. The Father, at last, will approve everything. He is the 'eudokôn’, the benevolent approver. He starts the Great conversation and he closes it, but this happens out of time, in the eternal reciprocity of Father, Son and Holy Spirit.

The proper share of each of the three Persons in the bringing about of the plan of the divine economy is visualized in the delicate way Rublev posits the Angels. Both of them are directed towards the Father. It is clear that the whole composition and movement of the icon starts from the left angel and returns to him. His upright stature, and the fact that he exceeds the circumscription of the hidden circle, the inclination, the glance of the middle and right angels towards him, give evidence hereof.

2. The white table

The table, around which they are seated, is at the same time the subject of their conversation. It is the starting point of a sharing of divine life with a different world. Creation is at the heart of the divine conversation. The table symbolizes creation.

The table has two main characteristics: it is square and it is white.

The table is square: this points to the difference which God installs by creating. Creation is not an extension of the godhead, but is called into being as 'different’ from God. From old the square form symbolizes the created world in antagonism with the circle, which symbolizes the divine and uncreated world.

The table is also white. This quality points to the innate goodness of creation. Creation shares in and manifests the goodness of the Creator. Although in the Greek mentality matter and wickedness are linked, the church fathers have countered this position vehemently. Creation, history and matter are vehicles of God’s goodness and beauty, of God’s power and love. Nothing in them is bad.

The white table is symbol of the goodness of creation. Creation carries the imprint of God’s beauty and love. In creating God shares goodness and beauty with all that exists.

In the whiteness of the table are also expressed the Holy Scriptures, the second way wherein God manifests himself. Holy Scripture, is in fact the first exegesis by man of the hidden revelation present in history and creation. This exegesis results in the words, narratives, prayers and prophecies of Holy Scripture. Man gives expression to the marks and traces of God he discovered and discerned within them (= history and creation).

God himself approved the reading man has made and He makes the human wording capable to express the hidden mystery in it. He approves the human discoveries and appropriates them as His word Therefore, in the liturgy, although the Scriptures are product of human wording, we conclude their reading with 'Word of God’.

For the fathers Scripture is a prolongation and an echo of creation.

Maximus Confessor, Amb. 33.

Or one could say that the Logos 'becomes thick’ in the sense that, for our sake, he ineffably concealed Himself in the logoi of beings, and is obliquely signified in proportion to each visible thing, as if through certain letters…

Or one could say that the Logos 'becomes thick’ in the sense that, for the sake of our thick minds, He consented to be both embodied (in material creation) and expressed through letters, syllabes and sounds (in the Scriptures), so that from all these He might gradually gather those who follow Him to Himself… bringing us for His own sake into union with Himself by contraction to the same extent that He has for our sake expanded Himself…

So we can conclude: the square table directed us, in a first stratum, to creation, and, in a second stratum, to its logic extension into Scripture. The whiteness we discovered as the symbol of the goodness and beauty of God, as a secret message present in them, as His secret presence in the elements of Creation and in the words and narratives of Scripture. The condition and themes for the dialogue with man are displayed in these first phases of God’s self-revelation.

Ephrem the Syrian, Hymn on Virginity 28, 1-2

Who has ever sung the wonder and the miracle

and sounded altogether myrads of strings,

and mixed into wisdom the old

and new with the natural?

The image of the Creator was hidden in them;

upon them openly You portrayed Him.

FRom all of them appeared the Lord of all

and the Son of the Lord of all.

3. The threefold blessing

The goodness of creation is echoed by the threefold blessing of the three Persons. It points to Genesis, where creation is clearly qualified as good at each day of its coming about. The blessing is expression of the divine approval. The created world is offered to man as an environment where-in the goodness/blessing of God has to be discovered. It is like a vineyard and the lord did everything possible and gave it as a habitable world to mankind in order to guide and attract it to Himself.

But the work of Gods coming in love and truth does not end up here.

4. The center of the table

· The upright man in the center of creation

What do we see at the center of the table? Or rather what should we see there, what can we expect to see there? Normally the upright posture of man should be there.

Man, indeed, introduced within creation at the sixth and last day, was meant by God to be the culminating artefact. He was meant to be the intendant and representative of God himself in the midst of time and matter.

God — what He did not with the rest of creation — in creating man, came down Himself and modeled man by his own hands and made him alive with his own breath. By this He gives a special mandate to man: he should be the gatherer of creation and direct it into a unifying movement of praise and thanksgiving around and towards the Creator. He received the task to harmonize, by putting God in the midst and to lead everything, step by step, into God’s own atmosphere. He should reveal, through his understanding (contemplative capacity) and by the quality of his intercourse with circumstances and his use of matter and nature, the hidden treasure lying in creation.

By his proper constitution, symbolized in his upright stature, being in the middle, between matter and spirit, he is meant to be the natural link between the material and spiritual world, experiencing both dimensions in his own bodily and spiritual existence. Man should confirm creation in its deepest truth: in its natural tension towards God, as St. Paul says in the letter to the Colossians: “Everything is created for Him and towards Him”.

In this task man was hoped by God to engage himself by his free choice to which God invited him by giving the commandment not to eat from the Tree of Knowledge: “If you will eat of this tree, you cannot stay alive”.

· The dead animal in the center of the table

If, after these considerations, we look at the icon, we do not find the upright posture of man. Instead we find the chalice with the dead animal inside, the offering of the calf by Abraham.

We remember that – after having eaten of the forbidden fruit, which is the symbol of man’s turning towards himself and his primitive and egoistic needs of well-being and well-feeling, and points to the whole richness of creation – how man directed it towards himself, and by doing this, destroyed its beauty and innocence.

God clothed the first couple with animal skins, as a sign of their regression – by their proper choice – into a life under the tyranny of their biological instincts, which man has in common with the beasts. It is common knowledge that the Fathers of the Church, in considering man’s indulgence, understood it as a kind of bestialization of his nature. The fact that God clothes man with animal skins is a kind of handing over of man to his animal nature. This experience is largely expressed in Christian art. The fallen man is represented in animal skins.

But in the mean time we discover, in the gesture of God clothing the lost first parents, something of his loving condescendence and mercifulness towards mankind.

Indeed, God gave not up man. Instead he pursued him, looking for new occasions to attract him.

The animal represents the biological part of man – the 'old man’ as scripture calls it – that has to be put to death so to open up a new way of existence, in order to change it – like a garment that we strip out – for another way of life: the robe of glory that we were wearing originally and that we had lost.

5. The Chalice

The fact that the dead animal, the immolated animal, is laid down in a chalice and is set in the middle of the table, leads us quite naturally to the idea of sacrifice and offering. Indeed, the animal did not just die. It was immolated by Abraham as a gift for the divine visitors.

The chalice itself also adds something to the message. Besides the connotation of sacrifice, the chalice gives support. It is the symbol of God’s hand, stretched out underneath all the changing circumstances and attitudes of human life. Even sinfulness cannot make us fall out of the outstretched hand of God. Even after the fall God did not abandon men. The whole amount of prayers and prophecies confirm this belief, that was alive even in the deepest abysses of human existence.

Psalm 130

Out of the depths I cry to thee, O Lord;

Master, listen to my voice;

let but thy ears be attentive

to the voice that calls on thee for pardon.

If thou, Lord, wilt keep record of our iniquities,

Master, who has strength to bear it?

Ah, but with thee there is forgiveness;

be thy name ever revered.

I wait for the Lord,

for his word of promise my soul waits;

patient my soul waits,

as ever watchman that looked for the day.

Patient as watchman at dawn,

for the Lord Israel waits,

the Lord with whom there is mercy,

with whom is abundant power to ransom.

He it is that will ransom Israel from all his iniquities.

In that sense the chalice is also linked to prayer. When we lift up our hands in prayer we ourselves take on the form of a chalice, because true prayer has always the quality of a sacrifice as Ps. 141 expresses it clearly.

Now we are able to qualify the chalice with the immolated animal as an image of offering: we offer our fallen nature to God. This we actually do when we immolate the animal in us by struggling actively and freely against the passions, trying to fulfill the commandments, actively and with all our strength. Also we do this by accepting freely the purification to which the different circumstances of life give us the occasion, when they overcome us involuntarily. But also, by entrusting our human weakness, incapacity and sinfulness to the mercifulness of God, all this by embedding our efforts, struggle and pain in prayer and hopeful supplication.

Isaac the Syrian , I, Homily 21

Blessed is the man who knows his own weakness, because this knowledge becomes to him the foundation, root, and beginning of goodness. (...) But no one can perceive his own infirmity if he is not allowed to be tempted a little, either by things that oppress his body, or his soul. (...) And again, whenever he looks over the multitude of his devisings, and his wakefulness, his abstinence, the sheltering, and the hedging about his soul by which he hopes to find assurance for her, and he sees that he has not obtained it; or again , if his heart has no calm because of his fear and tremblings: then at that moment let him understand that this fear of his heart shows and reflects that he is altogether in need of some other help. For the heart testifies inwardly, and reflects the lack of something by the fear that strikes and wrestles within it. And because of this, it is cinfounded, since it is not able to abide in a state of surety; for God’s help, it is said, is the help that saves.

When a man knows that he is in need of divine help, he makes many prayers. And the more he multiplies them, his heart is humbled, for there is no man who will not be humbled when he is making supplication and entreaty. 'A heart that is broken and humbled, God will not despise’. Therefore, as long as the heart is not humbled, it cannot cease from wandering; for humility collects te heart.

But when a man becomes humble, at once mercy encircles him, and his heart is aware of divine help, because it finds a certain power and assurance moving in itself. And when a man perceives the coming of divine help, and that it is this which aids him, then at once his heart is filled with faith, and he understands from this that prayer Is the refuge of help, a source of salvation, a treasury of assurance, a haven that rescues from the tempest, a light to those in darkness, a staff of the infirm, a shelter in time of tempeations…. and to speak simply: the entire multitude of these good things is found to have its entrance through prayer.

(...) All these good things are born to a man from the recognition of his own weakness.

6. Christ joins and takes our place

At this moment the symbolism of the icon leads us into another atmosphere. Into a liturgical, sacramental atmosphere. Indeed, all this happens when, during the Eucharistic celebration, we bring the gifts of bread and wine to the altar. In these gifts we enclose all our efforts, pain, failures and weaknesses. But also our prayerful hope on God’s mercy. The chalice with its 'weak’ content is the image of the confident sinner, relying on the mercifulness of God.

The gift of our poor lives and efforts is then taken over by Christ. He joins Himself to us, takes upon him our weakness, and carries the sins of the world. It is He, together with the whole of humanity, who lays himself down in the sacrificial cup and on the altar, culmination point of the whole of creation, as the Lamb of God that takes away the sins of the world.

The gift of our poor lives returns to us, enriched by the self-emptying of the Lord, as food and drink for eternity.

7. The Great counsel and the decision to save mankind.

At this moment we can look back and consider the Great Counsel where everything began; where the decision was made to create, and to speak, after the fall, words of consolation and prophecies of hope in the Scriptures and give us words to pray and to entreat the Lord of mercy.

At the end the ultimate decision was made to come down towards us in the person of the Son and take up the fate of humanity until the end, partaking in our death for the remission of sins. The heavenly decision embraces the whole Oikonomia, from the creation until the cross, in order to open up eternal well-being in God for mankind. The Holy Spirit was sent in order to open our eyes for the light that shone forth in Him, who was not held in respect, but nevertheless was more beautiful than man and was with God and was God.

8. The altar, sacrament of the heavenly banquet

Indeed, the table of creation is cumulating in the Eucharistic altar which is the sacrament of the table of the heavenly banquet. We see clearly the Three divine persons waiting for somebody. The front-side of the table is unoccupied. It is ready to receive the one since all eternity waited for: the healed, restored and renewed man, who joined his life to that of Christ, who believed in Him, and who, with Him and with the help and grace of the Holy Spirit, made of his life, of his weak life, a reciprocal sacrifice of love.

The whole icon emphasizes this openness, this quality of invitation. The inversion of the perspective, especially apparent in the footstools, strengthens and underscores this openness. We are invited to enter and to take the place we were invited to from the very beginning, and to join the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit to celebrate the eternal banquet with Them.

Indeed, the target of God is man, and the reason why he created is man, in order to make shine forth the divine light in a community of love between God and man.

9. Man the celebrant of a cosmic liturgy

Man can approach the altar now, which is, we remember, the condensation of the whole creation. The place man is invited to take, is the place of the celebrant (the side with the opening for the relics is the side where the celebrant takes place.) Now man is confirmed in his vocation: to link the whole created world as a gift of praise and thanksgiving with God and introducing it, by his regained freedom, into the community of Father, Son and Holy Spirit. He realizes forever his priestly vocation. He becomes the celebrant of a cosmic liturgy, the proestôs of a cosmic sacrifice of thanksgiving to the Giver of all.

10. The upper register of the icon

As a kind of conclusion and recapitulation we find in the upper register of the icon three elements, symbols, which in a certain sense resume what we discovered until now.

Above the right angel we see the mountain. It refers to the mountain Abraham went up to overlook the condemned cities of Sodom and Gomorrah, together with the central angel, while the two others admonished Lot to leave the city. But larger than that, the mountain is a symbol of the way of man towards God. To climb the mountain is a metaphor of the journey humans make through life towards their destination in the height, towards God in heaven.

The Holy Spirit, the right angel, as shows the position of his blessing hand, deeply involved in the reality of creation, is sent into in the world. He is revealed as the Helper, the Comforter, and the Sanctifier. It is He who accompanies men throughout their lives, guiding and supporting them during their journey to the top, during their pilgrimage on earth, to their ultimate destination.

Arriving at the top, man experiences the impossibility to go further. A kind of emptiness shows up before him and he is compelled to abandon all activities, left to his faith and his hope and love. This is the moment to sacrifice all his life and to abide in faith.

At that moment the only possible activity is to wait in darkness, entering a kind of death, an experience that the Fathers link to the cross, to the abandonment of Christ, dying on Golgotha. That’s why the mountain inclines towards the tree, ends up in the tree. The tree, initially the oak of Mamre, becomes here the symbol of the cross and we find it right above the angel of the middle, who is identified as the Son, the outworker of the plan of Salvation on the cross.

The tree also is bent to the left.

Having extended himself on the cross (equivocal with the offering of ourselves on the altar), and having completed the way through life with the help of the Spirit, waiting in hope and love, at the time God provides, man will be granted access to the house of the Father, where there is room for many. He will welcome man in due time.

We notice how the house is opening up towards the right as an image of welcoming the human pilgrim who completed his journey, and is allowed into the house of the Father. There the festal meal is ready, there man and God celebrate the ultimate feast of the victory of love. All men, together with the whole creation, are assembled at the table of the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit.